Get the most out of your OKRs by using Tana

Basics of OKRs

What are OKRs?

OKR stands for “Objectives and Key Results” – a management methodology invented by Andy Grove at Intel in the 1970s and popularized by John Doerr through is book “Measure what Matters” in which he tells the stories of how OKRs helped organizations like Google to become the dominant players that they are today.

The idea behind OKRs is to align everyone in an organization to work towards the same goal and prevent “random work” that looks and feels productive but does not contribute to achieving a company’s or team’s mission.

If you want to test using OKRs in Tana, check out the OKR template.

Benefits of OKRs for High-Expectation Leaders

Why use OKRs? What’s the benefit of adopting this approach?

What makes OKRs great is that they allow you to create focus and alignment in your organization. They also give you a way to really show and elicit commitment to the work being done, as well as tracking what everyone is working on, what their highest impact areas are, and providing an incentive for stretching what everyone is trying to do.

When OKRs Might Not Be the Best Fit

OKRs aren’t a silver bullet that will deliver exceptional results in every single circumstance:

Clue 1: Insufficient buy-in

As with any process or tool that you’re introducing to your team or wider organization, you’ll need sufficient buy-in so that people take it seriously and actually do what’s required to make it work. There’s no fix for half-hearted attempts to write OKRs, or using other tools for that matter.

Clue 2: Fitting OKRs in project management

One common question is “what is OKR in project management” – and the answer is that OKRs aren’t the right tool for project management in the first place. Why is that? The idea behind OKRs is to set, communicate and monitor organizational goals in regular intervals. In essence, OKRs generate projects (called “initiatives” in this context) with the purpose of achieving a specific key result. But you would not generate OKRs within a project or initiative.

Clue 3: OKRs for measuring continuous indicators

Another common question is what the difference between OKRs and KPIs is. In short, OKRs are actionable, ambitious and time-bound – whereas KPIs are continuous indicators for the ongoing performance of a particular function or process. KPIs ask the question “how are we doing?” while OKRs ask “what do we want to achieve and how do we get there?”

Clue 4: OKRs for performance reviews

Finally, OKRs aren’t the best fit when you are looking for a tool to feed performance reviews of your team. For a time it was common to set OKRs not just on the organizational level but to create objectives and key results for every individual team member. This turned out to be not a good idea, because it turned key results more into task lists than into ambitious targets that would inspire exceptional performance.

One key idea for OKRs in general is to make them so ambitious that you achieve them only 70% of the time – which in turn means you and your team can work really, really hard and still not “succeed”. But that’s by design and should not negatively impact the performance review. Because if it does, it will lead to one thing: the next rounds of key results will be made more and more conservative until 100% success is always achieved, snuffing out any ambition and making OKRs virtually useless.

OKR prep and planning

How to write a good OKR

The key to writing good objectives and key results is to make them actionable, ambitious and time-bound. What does that look like?

OKRs are about alignment across all levels

Before we dive into the specifics of writing good objectives and good key results, remember that the idea behind OKRs is to align everyone in what they are working towards, achieving the company vision and mission. Good OKRs make it clear to everyone involved how their work contributes to this, and every team and team member can track their work all the way up the chain to the goals of the company.

3 to 5 OKRs per team – not more

Another important question is “how many OKRs should a team have?” and the anwer is: about three to five. Anything more than that diffuses your energy too much and becomes hard to actually make progress on.

How to write good Objectives

Objectives are for the “What”

A good objective gives the “what” and does so in a tangible and unambiguous way. When you write your objectives, one good question to ask yourself is “Could a competent outsider come in at the end and judge whether this has been accomplished or not?”

Go for ambition AND realism

In addition, make sure that your objectives are ambitious and realistic at the same time. This can take a bit of practice to get right. There is a natural tension between being ambitious and realistic and it is fine to occasionally have objectives that have to be met with 100% certainty.

Choose between “committed” and “aspirational” OKRs

Some organizations therefore distinguish between “committed” and “aspirational” OKRs. Committed OKRs will be hit, even if that means adjusting the schedule or increasing the available resources substantially. Aspirational OKRs on the other hand will get hit only with 70% certainty – most will be met, but there’s high variance between them over time.

Now what’s a good objective look like compared to a bad one?

Here’s a bad objective: “Make our company the best place to work”

Sure, this is aspirational, but it’s too vague to be useful. A better objective would be “Become recognized as a leader in employee satisfaction and retention” – still aspirational, but much more concrete in that we’re explicitly focusing on “employee satisfaction” and “retention.” Note that we’re not specifying more than that though: we’re giving direction without fixating on a specific metric. That’s what we’ll do in the Key Results section.

Let’s look at another example: “Improve our social media presence”

Again aspirational, but again too vague. Better: “Significantly expand our engagement and reach on social media to drive customer acquisition”. We’re giving direction, we’re aspirational, and we’re also connecting the objective to a larger Why. This is important both for overall alignment and for motivation.

Once you have a “what”, the question is how you get it, and that’s when you start designing your Key Results.

If you want some help in reviewing your OKRs, test the OKR AI agent in the OKR template.

Designing Measurable Key Results

Key Results are quantifiable

The defining characteristic of key results is that they are quantifiable. What does that mean?

Let’s look at our example objective from above: “Become recognized as a leader in employee satisfaction and retention.” How do you quantify this?

From the objective we have three hints that we now need to operationalize.

- “Become recognized as a leader”

- employee satisfaction

- retention

What does “become recognized as a leader” mean precisely? Maybe there’s an industry association that surveys and recognizes the top 10 “best places to work” in the industry.

A first key result for our objective could then be “Get included in SurveyCorp’s ‘Top 10 Places to Work’ list”.

Beware of “lagging indicators”

The problem is that being included in this list is what’s called a “lagging indicator” that we only have limited control over. Being on the list is a result of actions we’re taking, and whether we actually get included is out of our hands. Instead, when writing your key results, focus on writing concrete “leading indicators”, things that you have more direct control over.

Better key results would look like this:

- KR1: Increase average employee satisfaction by 8%

- KR2: Increase employee retention rate from 90% to 95%

Choose “outcome key results” over “input key results”

Now, you could quibble here and say “well, employee satisfaction is a lagging indicator too!” – and you’d be right. It is, however, a lagging indicator that you can directly influence. This is an “outcome key result” and these can be really useful in allowing a team to dynamically come up with the best solutions for achieving them. One of the most common pitfalls of OKRs is actually focusing on “input key results” that read more like concrete task lists that don't allow dynamic adjustment during the work.

Calibrate for a 70% success rate

As mentioned previously, ambition in setting objectives and key results is one of the key factors for getting the most out of them. But calibrating ambition is a skill that needs to be developed by everyone responsible for setting OKRs. A general rule of thumb for calibration is that you want to succeed (achieve your key results) around 70% of the time. If you succeed more than that, you aren’t ambitious enough and if you achieve significantly less, you’re overly ambitious.

Implementing OKRs

Prevent “goal drift” by having one responsible person per Key Result

When implementing OKRs, one issue that often comes up is that they are hard to connect to the initiatives that are supposed to achieve them. It’s all too easy to experience goal drift where in the course of making things happen the goal drifts away from what was originally set out in the objectives and key results.

The reason for this is two-fold: one mistake is to not make a single individual responsible for the Key Result – without a directly responsible individual, veering off course is all but guaranteed. The second reason is harder to spot because it depends on the way we work and in particular the reliance on files and folders.

OKRs die in silos – connect them to everything

That sounds like an unusual thing to blame, so let’s zoom in a little. Most often OKRs are written down in a document that is then (occasionally) referenced. This document, however, is not connected to the places where the work happens. That work is happening in code bases, issue trackers, Excel sheets, project management apps and a hundred other places – all separate from the document where the OKRs are written up.

This in turn means that people see the OKRs only when they consult the document, for which they have little reason in the normal course of the work that they are doing. That means that unless someone makes it a habit to pull up the OKR document in every single meeting, it’s likely only consulted in the meetings that are explicitly about the OKRs, or in short: not often enough.

Implementing OKRs with Tana

This is where an app like Tana can fundamentally transform the way we work and get things done. Because in Tana, you can connect your OKRs to the actual work at every level. OKRs are never siloed away in some folder nested in a deep dark place that no-one ever visits. Instead, OKRs can be visibly connected to every single initiative going on, every meeting you hold and stay visible during the work and all the meetings surrounding it.

See every Key Result during every 1:1

Without going into the weeds here, consider the example from above: we have the objective “Become recognized as a leader in employee satisfaction and retention” and we have the key result “Increase average employee satisfaction by 8%”. Julia is one member of our team that is directly responsible for this key result. If you have a 1:1 with Julia, Tana can pull in every Key Result and its connected Objective automatically – no need to reference some document that you don’t know where you saved it exactly.

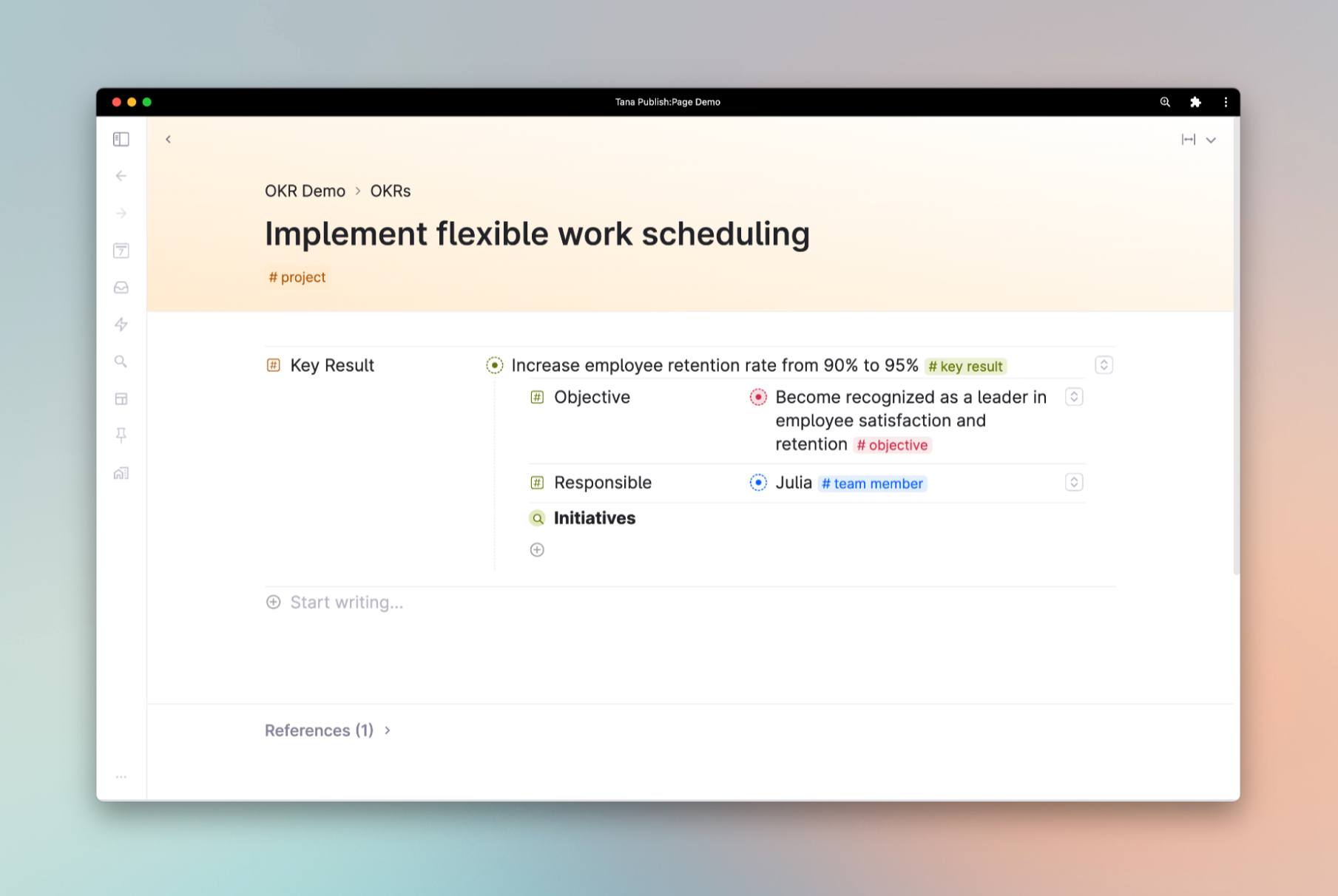

Every project shows it purpose

We also have a project/initiative “Implement flexible work scheduling” that is supposed to work towards achieving the key result. In Tana it is trivial to connect this project/initiative to the key result and by extension the objective. That means wherever we’re looking at the project/initiative, we always have the key result in sight, we see who the directly responsible individual for the key result is, and what objective the key result is part of. Our work therefore never experiences goal drift because we always have the overarching objective right in front of us.

Conclusion

OKRs are a powerful tool for organizational focus, alignment, and commitment. Following OKRs prevent aimless work, and are important for ambitious goal-setting. Tana is a practical solution to integrate OKRs seamlessly with your projects, tasks and more.